European powers gained interest in the Indian subcontinent by the late fifteenth century. Competing powers, including the Dutch, French, Portuguese, and British, sought to control valuable resources and trade routes centered around spices, textiles, and tea. The British ultimately established their dominance in the subcontinent when British crown rule was formally declared in 1858 following a protracted nationalist uprising known as the Sepoy mutiny. The next ninety years would be especially turbulent for India and the world.

India’s largest political party, the Indian National Congress (INC), was founded shortly after 1885. The party was central to the eventual independence movement. Although the ideology was not clearly defined from the beginning, World War I seemed to be a key turning point. India volunteered over 1.5 million troops to British war efforts, which ultimately led to more than 45,000 casualties and near-bankruptcy for India. Some leaders hoped Indian war efforts would lead to increased sovereignty from the British, but that was not the case. Post-World War I angst helped transform the INC into a leading independence movement that included both prominent Muslim and Hindu voices. Jawaharlal Nehru, Mohandas Gandhi, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah were some of the key figures. Gandhi returned to India in 1915 after a short stay in South Africa following his law school graduation. His experience with racism as a new lawyer transformed his outlook and inspired him to return home to India and promote independence via peaceful resolution. Likewise, Nehru, a self-proclaimed nationalist, was also a British-educated lawyer and returned to India after completing his education. Jinnah, a Muslim and recently graduated British-educated lawyer, worked at the Bombay High Court and emphasized Hindu–Muslim unity.

Shortly after the end of World War I, growing tensions and riots between Hindus and Muslims created a sense of unease among the Muslim minority. Ideological and political differences between the groups had risen to alarming heights, as both religious groups sought to gain political and geographical representation. Amid the growing tensions, the INC firmly declared its commitment to secularism and the Gandhian idea of Satyagraha (peaceful civil disobedience). This political strategy was intended to be inclusive, but it left some Muslims, specifically the leaders of the All India Muslim League, disillusioned. Jinnah considered Satyagraha to be political anarchy.1 Until this point, Muslims and Hindus had been relatively united under the banner of independence, as demonstrated by the 1916 Lucknow Pact agreeing to establish quotas guaranteeing representation of Muslims and other minorities in public offices. That unity quickly started to dissipate when Jinnah resigned from the INC, citing his disagreement with Satyagraha as a strategy. Jinnah withdrew from politics for the next decade, only deciding to return after the election of 1937, after the Muslim League gained only 6.7 percent of votes and failed to win the majority in any province, including those with a Muslim majority. This event was transformational for Jinnah and overturned his long-held belief that Muslims could be protected in a majority Hindu country. Jinnah’s new political strategy was to promote a two-state solution, one for Muslims and one for Hindus. This new political strategy coincided with an awakening of Jinnah’s own Muslim identity, a shift away from his earlier sense of broad secularism.2

Calls for independence amplified during and shortly after World War II as Indian soldiers again entered a world war fighting on behalf of the British. The Congress Party demonstrated its disapproval by initiating a campaign of civil disobedience against the British. Both Gandhi and Nehru were eventually arrested for their displays of opposition. During their incarceration, Jinnah nearly consolidated support from the Muslim community, identifying himself as the fierce protector of Muslims in the subcontinent. As World War II came to an end, riots and interreligious violence between Hindus and Muslims was occurring at alarming rates. Public animosity between Gandhi and Jinnah, in addition to inflammatory speeches by regional politicians, further inflamed communal tensions. Muslims and Hindus fought to control neighborhoods that had historically been religiously diverse. The future was increasingly unclear, and each side held the other responsible for the uncertainty.

Ultimately, estimates suggest that one to two million people perished from violence or illness during the Partition.

Exhausted from World War II, the British were ready to withdraw their personnel. In 1946, one year after the war ended, nationwide elections were held with both the Muslim League, led by Jinnah, and the INC, led by Nehru, on the ballots. Compared to 1937, the Muslim League did substantially better, winning the vast majority, 90 percent, of Muslim districts. Jinnah took this result to mean widespread support for his call for a separate Muslim homeland.3 On August 14th, 1947, the birth of Pakistan (the “land of the pure”) was announced, and a partition line splitting the subcontinent into two was hastily drawn by Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a British bureaucrat with limited background knowledge of India. Radcliffe and his British cabinet mission divided the Indian provinces on the basis of their religious makeup; the Hindu majority states in the middle would become India and the two noncontiguous Muslim majority provinces on each side of India would become East and West Pakistan. What followed was the largest known movement of humankind, around fifteen million people, as Hindus from Pakistan relocated to India, and Muslims from India to Pakistan. Limited oversight by the withdrawing British forces and a chaotic new independent government were unable to oversee the migration and provide ample security. Increased religious tensions and poor execution of the Partition led to widespread violence among the migrants. Ultimately, estimates suggest that one to two million people perished from violence or illness during the Partition. Following the bloody Partition and legacy of communal violence, the newly independent government of India, led by Nehru and the INC, was determined to enshrine secular and socialist principles in its Constitution. On January 26th, 1948, India adopted its Constitution, declaring India a secular state. The INC wanted to ensure that the bloody historical legacy between Muslims and Hindus would not become a regular feature of Indian society. India’s secular identity separated itself from Pakistan’s religious- based identity. Unfortunately, the Partition failed to resolve tensions between Hindus and Muslims. By October 1947, India and Pakistan were already at war with one another over the state of Kashmir.

Kashmir

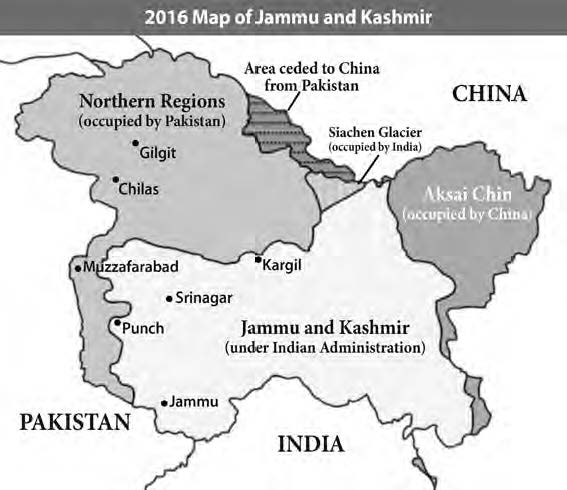

Upon independence, there were 565 princely states throughout India. Princely states were independent polities and not formally considered part of British India. Following the Partition, princely states were given the decision to select which country to join. For most princely states, this was a simple decision; Muslim-majority states in close proximity to Pakistan joined Pakistan, while Hindu states joined India. One leader, Maharaja Hari Singh, had difficulty deciding which side to join. Singh was a Hindu leader of the primarily Muslim state of Kashmir. Before he could make his decision, Pakistani and tribal forces attacked and occupied the princely state. The maharaja turned to India for help. India agreed to intervene on the condition that Singh sign an instrument of accession agreeing to cede Kashmir to India. The maharaja agreed, but the conflict continued until both parties went to the UN to resolve the conflict in April 1948. Both parties agreed to the resolution (Resolution 47), and eventually, a line of control was adopted, with India gaining two-thirds of Kashmir’s territory (India-occupied Kashmir) and Pakistan obtaining one-third of the territory (Pakistan-occupied Kashmir). The resolution included several conditions, including withdrawal of Pakistani forces, a reduction in Indian military presence, and an eventual plebiscite allowing Kashmiris to vote on the issue. Although both sides had objections, India and Pakistan agreed to the resolution and brought an end to the war. Despite the original agreement, the Kashmir conflict continued to be a defining issue between the two countries in the following decades. Since the initial 1947–1948 war, three additional wars have been fought over the territory, with no clear resolution in sight.

Kashmir remains a central issue for distinct reasons that reflect the founding philosophy of both countries. To Pakistan, a Muslim-majority province should be governed by a country founded as a Muslim homeland in the Indian subcontinent. To India, governing a Muslim-majority region solidifies its identity as a secular and multicultural state, and honoring the initial wishes of Singh. These conflicts are further amplified by the rise of Hindu nationalism in India and Islamic extremism in Pakistan, with both sides claiming Kashmir as an integral part of their homeland.

The Rise of Hindu Nationalism

Although Kashmir was a defining issue between India and Pakistan and Hindu and Muslims, the two-state solution failed to resolve internal tensions. Despite India’s constitutional foundation as secular, strict adherence to Hindu and Islamic identities rose in popularity, specifically in the 1990s. Riots between the groups, in addition to Sikhs and Christians, occurred throughout the country from independence onward. The Kashmir conflict seemed to exacerbate the tensions. During this time, the ideology of Hindutva, a political movement embracing Hindu fundamentalism and identity, gained prominence. Likewise, Islamic extremism, within Kashmir and throughout India and Pakistan, also gained popularity.

The INC remained the primary party in power and maintained its commitment to secularism as a central tenant for nearly half a century. No party could gain enough power to challenge the INC until the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The BJP’s central philosophy centers on Hindu nationalism. From 1947 to 2000, the INC held the majority of seats in parliament, with the exceptions of 1977–1979 and 1996–1999, when the BJP gained a majority of votes. The increasing popularity of the BJP was not coincidental and occurred alongside increasing tensions between Hindus and Muslims, as detailed below.

Just as Mumbai was recovering from the 1993 riots, it experienced the worst terrorist attack in its fifty-year history. A series of car bombs detonated throughout the city and left 257 dead and over 1,000 injured. The attacks were believed to be coordinated by Muslims involved in the Indian criminal underworld. Following the attacks, Hindu militant groups such as the VHP and the Shiv Sena rose in popularity to fight what they believed was a growing assault on Hindu values. As more Hindus feared terrorism at the hands of Islamic extremism, they began to reevaluate the constitutional enshrinement of secularism.

In 1996, the first election since the 1993 riots, the BJP won a majority of seats in the parliament for the first time. The BJP ran on a platform of Hindu nationalism and pushed for the banning of cow slaughter, a meat eaten by Muslims, as well as reclaimed Kashmir as fully Indian.4 The BJP continued to gain in popularity at the national and state levels, as well. In the state of Gujarat, a key figure named Narendra Modi took office as the chief minister in 2001. Because he grew up impoverished and from a low caste, Modi was an inspirational figure to many Hindus and low caste members. Modi is a lifelong member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), an ultraconservative Hindu organization devoted to preserving and restoring Hindu identity in India, particularly through the establishment of a Hindu state. The RSS, the radical Shiv Sena, and VHP remain closely tied. Many members of these organizations become leaders in the BJP.

In 2002, Modi’s name would be brought to national and international prominence when a new set of Hindu–Muslim riots occurred in the state of Gujarat. As a train of Hindu pilgrims was returning from Ayodhya, it was attacked and burned by a mob of 1,000–2,000 villagers that were believed to be Muslim. Sixty pilgrims died in the attack. The train attack led to widescale riots in Gujarat. What made these riots so controversial was the response by the BJP government and Modi. Human rights organizations and scholars have claimed the BJP was complicit in the riots and failed to respond appropriately; some scholars have even called it pogroms, or “ethnic cleansing.”5 Over 2,000 people, the majority Muslim, were killed in subsequent rioting. Another 150,000 were displaced and ended up in refugee camps. In 2005, Modi’s ties to the riots led the United States to deny him a diplomatic visa and revoke his existing visa. Modi was the first official to ever be denied entry under the International Religious Freedom Act, which prevents US entry of a foreign government official responsible for violations of religious freedom.6 An investigation by a Supreme Court-appointed panel in 2012 ultimately found Modi’s actions not to be prosecutable; however, the report still found Modi to have a discriminatory attitude that justified the killing of innocents.

The controversy surrounding Modi’s role in the riots ultimately did not tarnish his reputation in the eyes of the BJP. The BJP named Modi as their candidate for prime minister in 2013. Throughout the campaign in the following year, Modi attempted to distance himself from the Hindutva rhetoric he relied on in the past, invoking secularist language reminiscent of Nehru. Instead, the primary focus shifted to Gujarat’s rapid economic development under Modi. However, the BJP as a whole still invoked nationalist rhetoric, including leaders calling for Muslim eviction from Hindu areas and for critics of Modi to move to Pakistan. Cow slaughter ban proposals remained on the agenda, and Modi would not condemn these remarks in his campaign. He also refused to apologize for the government response to the 2002 riots when asked if he was sorry.7 Modi and the BJP went on to win an astounding majority in parliament, gaining 166 seats while the INC lost 162 seats, its worst defeat since independence. In 2014, Modi not only received a US visa, he was also welcomed by President Barack Obama at the White House and by 20,000 supporters at a Madison Square Garden rally.

The saffronization of India was well underway by 2014. Just as Hindu priests wear saffron robes, Hindu nationalists also adorn the color to signify their political and religious convictions. In the 2014 election, nearly every single district in northern and western India was won by the BJP. On the streets, vigilante Hindu groups such as the Bajrang Dal and VHP patrol neighborhoods throughout India with the intent of enforcing Hindu moral codes. Tactics utilized by this group include stopping trucks with cows being led to slaughter and beating or killing the driver, harassing couples for celebrating Western holidays such as Valentine’s Day, or attacking women for being dressed too liberally.8 Modi continued to distance himself from his ties to the RSS and other radical Hindu groups in his public speeches, but the BJP policies and leadership selection demonstrate that the party refuses to uphold secular values. Modi also published books during the campaign highlighting the lives and contributions of RSS members.

Perhaps the clearest indicator of the BJP’s ties to radical Hindu identity occurred in January 2017. At that time, the BJP selected Yogi Adityanath as the chief minister (governor) of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state and home to the Babri Masjid ruins. Yogi Adityanath is an Indian monk and founder of the Hindu extremist militant group Hindu Yuva Vahini. The Hindu Yuva Vahini has participated in many concentrated efforts, including public cow protection campaigns, fights against Hindu–Muslim marriages, and Ghar Wapsi, mass conversions of Christians and Muslims to Hinduism.9 Adityanath has a long association of calls for violence against Muslim communities, including a call to kill 100 Muslims for every Hindu killed.10 The appointment of a radical religious leader as the chief minister of the largest state in India signals the BJP’s intent to move away from the secular roots of the country, as well as tacit endorsement of violent strategies against minority communities.

Broader Implications Ethnic and religious violence is an unfortunately common experience throughout much of the world. However, the shift toward Hindu nationalism over the past few decades has potential security implications beyond domestic politics. For one, both India and Pakistan became nuclear states in 1998. Although India had been developing nuclear weapons since the 1970s, its 1998 test occurred under the direction of the newly elected BJP government. Shortly after, Pakistan responded with its own nuclear test. The tests resulted in international sanctions against both countries, but it did not eliminate the nuclear programs.11 By 1999, both states were engaged in another war in Kashmir, after Pakistani forces infiltrated the Line of Control. Known as the Kargil conflict, this standoff was the first instance of direct conventional warfare between two nuclear states, and perhaps the closest the world has come to nuclear warfare.

The rise of Hindu nationalism and BJP’s prominence has profound potential ramifications for India’s relationship with a nuclear-armed Pakistan. It is already evident that Hindu nationalists take a much more hard-line approach when it comes to security, especially as it relates to Muslims or Pakistan. This can increase the likelihood of conflict initiation between Pakistan and India, most likely in Kashmir. One particularly concerning stance is the view from both Pakistan and India on first-strike utilization. Generally, nuclear powers hold to the norm of only using nuclear weapons in response to a first strike, which results in what is traditionally referred to as mutually assured destruction (MAD).12 Because both sides know the other will retaliate, it prevents the other side from utilizing the weapons. Pakistan has always gone against this norm by maintaining that it will consider a first-use policy of nuclear weapons. In contrast, India has generally held that it will only utilize nuclear weapons on a second-strike, or retaliatory, basis. However, since the election of Modi, that stance appears to be shifting. In their 2014 election manifesto, the BJP said it is studying, revising, and reconsidering its nuclear program. The BJP also blamed the INC for scaling back the nuclear gains made under the 1999 BJP government. Under the INC, the nuclear program had shifted toward civilian energy, rather than defense-related expenditures. While the intent of the manifesto is not entirely clear, many nuclear scholars suggest that the language is a noticeable hard-line shift in Indian foreign policy.13 The BJP further redefined what “first use” means, claiming that the other side has initiated a response if they assemble, not just launch, their nuclear weapons. With two nuclear powers willing to use first strike, it substantially increases the chances of miscalculation. With a history of repeated conflict over a territory, including when both countries had weapons, it signals that nuclear deterrence may not be as effective in the Indian subcontinent.

The rise of Hindu nationalism also changes the dynamics of international relationships. Nehru’s foreign policy during the Cold War was nonalignment and heavy investment in international institutions, like the UN. At the end of the Cold War, India still maintained its distance from the US, forming military alliances with other countries. The United States developed closer relationships with Pakistan and China. In 2009, as part of Obama’s pivot to Asia strategy, India and the US began developing closer ties, including the US advocating for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council for India. The pivot to Asia and friendlier relations with India was mostly part of the US interest in counterbalancing a growing regional and global threat from China.

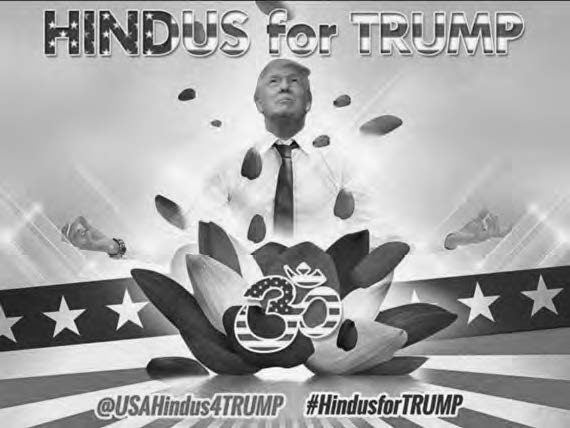

A more interesting development in the US–India relationship occurred in 2016 during the US election. Hindu nationalist parties began rallying behind Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump. The groups were invigorated by what they perceived as Trump’s hard-line stance on Muslim immigration and terrorism. Shiv Sena, the VHP, and other Hindu nationalist parties held large public prayer ceremonies for Trump.14 During election season, Trump became aware of his growing popularity among certain segments of the Indian population and used it in his campaign. Perhaps most interesting is the use of a Trump campaign ad by Shalabh Kumar, Chairman of the Trump campaign’s Indian American Advisory Council, appealing to American Hindus. Hindu symbology and music were used within the ad, and it concluded with Trump speaking in Hindi saying, “Ab ki baar, Trump sarkar,” meaning, “Next time, there will be a Trump government.”15 The slogan holds little meaning once translated, but the usage of it was significant because it was the same slogan Modi used in his 2014 campaign.

Trump’s support of Hindu nationalists may also be an attempt to check Islamic extremism in Pakistan. To India, Trump’s rhetoric and ties to Hindu nationalists can be seen as tacit support for a hard-line approach toward Pakistan. In late December 2017, Trump announced a plan to withhold military aid to Pakistan due to Pakistan providing a safe haven for terrorists. This announcement was applauded by India and marks a significant shift following decades of US military and economic support for Pakistan.

Hindu Nationalism: The Future?

The potential impact of Hindu nationalism does not necessarily end at India’s borders. Many Hindu nationalists believe that a proper map of India would include Nepal, Bhutan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.16 Hindu nationalists have even undertaken a campaign to rewrite Indian textbooks to change the maps to reflect what they believe are proper borders. It is unclear at present, but if this sentiment does result in a future expansionist foreign policy, India will be more likely to engage in conflict with Pakistan, other neighbors, and even possibly China. The Constitution of India still enshrines secularism, but the trend for the past three decades indicates it is moving toward Hindu nationalism. Nehru’s commitment to secularism was his declaration that India could be a peaceful, multireligious state. Jinnah maintained his doubts. With the increasing popularity and success of the Hindu Nationalist Party, we will soon know whether Jinnah was correct. ■

NOTES

- Nisid Hajari, Midnight Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015).

- M. R. Kazimi, ed., M.A. Jinnah Views and Review (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- Akbar Ahmed, Jinnah, Pakistan, and Islamic Identity: The Search for Saladin (Abingdon, England: Routledge, 1997; Reprint, 2005).

- Ranbir Vohra, The Making of India, 3rd ed. (Abingdon, England Routledge, 2013).

- Also see Martha Nussbaum, The Clash Within: Democracy, Religious Violence, and India’s Future (Harvard University Press, 2008); Ashutosh Varshney, Ethnic Conflict and Civic Life: Hindus and Muslims in India (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2002); Steven Wilkinson, Votes and Violence: Electoral Competition and Ethnic Riots in India (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2004); Paul Brass, The Production of Hindu-Muslim Violence in Contemporary India (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003).

- “No Entry for Modi into US: Visa Denied,” The Times of India, March 18, 2005, https://tinyurl.com/yb8az7gt.

- “Modi Refuses to Apologize for Gujarat Riots, Says Case Before People’s Court Now,” The Times of India, April 7, 2014, https://tinyurl.com/ya3gox9p.

- Paul Marshall, “Hinduism and Terror,” Hudson Institute, June 1, 2014.

- “What the Hindu Yuva Vahini’s Constitution Tells Us about Yogi Adityanath’s Regime in Uttar Pradesh,” The Caravan, March 27, 2017.

- James Crabtree, “If They Kill Even One Hindu, We Will Kill 100,” Foreign Policy, March 30, 2017.

- Michael Krepon, “Looking Back: The 1998 Indian and Pakistani Nuclear Tests,” Arms Control Today 38, no. 4 (2008): 51–55.

- Colonel Alan J. Parrington, “Mutually Assured Destruction Revisited, Strategic Doctrine in Question,” Airpower Journal 11, no. 4 (1997): 4–19.

- Zachary Keck, “Is India About to Abandon its No-First Use Nuclear Doctrine?,” The Diplomat, April 9, 2014, https://tinyurl.com/y8h5fwxm.

- Tej Parikh, “Why India’s Hindu Nationalists Love Donald Trump,” The Diplomat, February 28, 2017, https://tinyurl.com/yckblej2.

- “Official Trump campaign ad of ‘Abki Baar Trump Sarkar,” YouTube video, 0:30, posted by “Shalabh Kumar,” November 6, 2016, https://tinyurl.com/ycuxpqzk. 16. Al-Jazeera, People and Power: India’s Hindu Fundamentalists, 2015.

No comments:

Post a Comment